Value

Creation

January 2026

Overview

What happens after a deal? As a follow-up to our previous article “Behind a Private Markets Deal”, we aim to explore how private equity (“PE”) investors perform value creation, the act of monetising their ownership in portfolio companies (“portco”) to make a profit on their investments.

PE investors often invest in companies via fund vehicles. Such PE funds are considered General Partners (“GP”), meaning they manage the fund. They raise capital from Limited Partners (“LP”). GPs are tasked with returning capital to LPs after a period of time (typically 5-10 years), and thus face pressure to create value from their portfolio companies within this time frame.

PE investors measure the value created via the Internal Rate of Return (“IRR”) metric, the annualised rate of return on the investment. Typically, PE funds target a 20%-25% IRR benchmark across the fund, with variation depending on the fund’s investment thesis.

PE investors commonly create value via what we have termed the “Control, Create, Cash-Out” strategy:

-

Control: PE investors look to acquire a majority stake in a target company, which allows them to make unilateral decisions regarding the portco without interference from other shareholders.

-

Create: PE investors design a suite of operational strategies to grow the portco. The goal is to improve margins and ultimately free cash flow, which boosts the portco’s intrinsic Enterprise Value.

-

Cash-Out: PE investors look to sell their stake at more attractive valuations than at entry.

PE funds also may recoup capital via the following means (non-exhaustive), which are especially relevant if the fund finds it difficult to sell their shares:

-

Dividend recapitalisation: The portco takes out a loan, and the proceeds are distributed to the PE fund as dividends. This is usually done as a short-term way to distribute immediate capital, and may not be suitable for a long-term strategy as loans strain the portco’s ability to reinvest cash into growth initiatives.

-

Par value reduction: The portco reduces the par value of each share without changing the total number of shares. It compensates shareholders for the lost value by repaying the difference.

-

Share buybacks: The portco repurchases shares from shareholders, providing the PE fund with immediate return on their shares.

To illustrate how these concepts play out in practice, we will proceed to dive into two prominent examples of value creation in the Southeast Asia PE market.

Deal #1: Baring Private Equity Asia and Topaz Investment Worldwide’s SGD84m Investment in Courts Asia Limited

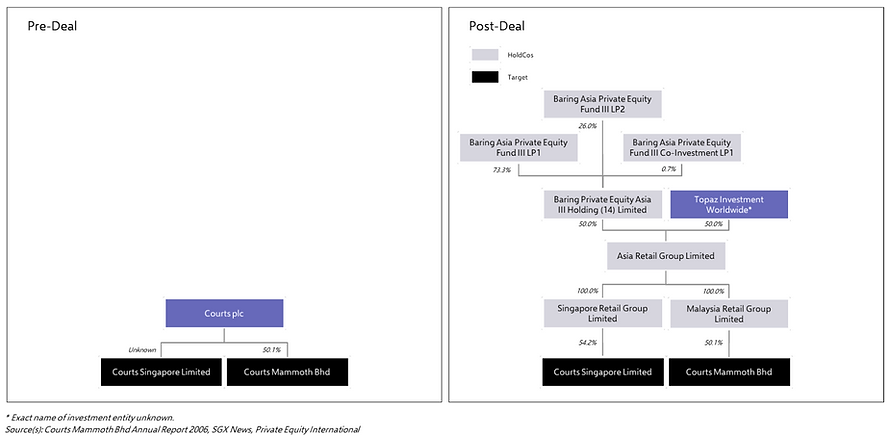

In July 2007, Hong Kong private markets investor Baring Private Equity Asia (“BPEA”) formed a consortium with Kuwaiti investor Topaz Investment Worldwide to acquire the following subsidiaries (the “Courts subsidiaries”) of Courts plc (“Courts UK”), then a renowned United Kingdom-based consumer electronics and furniture retailer:

-

54.2% stake in Courts Singapore Ltd (“CSL”), listed on the Singapore Stock Exchange (“SGX”)

-

50.1% stake in Courts Mammoth Bhd (“CMB”), listed on the Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad

From 2007-2009, the consortium bought the remaining stakes it did not own in CSL and CMB, delisting both entities. The combined valuation was reported to be approximately SGD84m. They were consolidated under the Courts Asia Pte Limited (“CAL”) entity in January 2010.

The acquisition was later seen as a success for BPEA, who partially exited CAL via an IPO on the SGX in October 2012, before gradually selling all its interests in the public market. Upon IPO, CAL had the largest market share in Singapore and the second largest market share in Malaysia by sales volume among IT, electronics and furniture retailers.

Control: Opportunism amidst chaos

In late-2004, Courts UK went into administration after a 15-bank syndicate demanded back loans amounting to GBP 280m. Analysts attributed this collapse to a mixture of a complicated corporate structure and a weakening pound.

Financial issues at the group level pressured management to sell their controlling shares in their overseas entities, including the Courts subsidiaries, to PE investors.

The Courts subsidiaries fared better, operating in a regional market with growing disposable incomes and a compelling business model of selling household items at bargain prices. However, their shares faced disappointing outlooks in the years prior to the acquisition. CMB faced an eroding market share due to being unable to evolve against the influx of foreign competitors, with its share price falling dramatically throughout 2004 and failing to recover since. CSL fared somewhat better as the primary Southeast Asian subsidiary with respectable topline growth, yet still faced a stagnant share price primarily owing to poor credit infrastructure.

These factors created an opportunity for BPEA to make one of their first investments into underperforming entities for an attractive valuation, with an intention to turn around the operations. BPEA took the view that the Courts subsidiaries were operating below potential and could get back on track with operational reshaping.

Create: Consolidation, credit and curation

While many value creation strategies were implemented under BPEA, we have chosen to discuss 3 notable ones:

Consolidating entities to grow margins

BPEA identified a margin growth opportunity by acquiring both CSL and CMB and consolidating them into one entity. From a topline perspective, CSL provided the stability of an established market, while CMB provided the upside of a developing market with a growing middle-class demanding household consumer products. Furthermore, BPEA saw the benefit of unifying both entities under a single leadership’s vision. For instance, the Courts subsidiaries identified Indonesia and Thailand as potential growth markets and had a minor presence in them prior to the consolidation. However, the Indonesia and Thailand operations were loss-making, facing difficulty in outdoing their competitors. BPEA closed down the Indonesia and Thailand operations, believing a single management team would allow CAL to focus on the core markets of Singapore and Malaysia. Moreover, it could learn from each other’s experiences operating the separate entities to craft a unified strategy to re-enter Indonesia and Thailand in the future.

From a costs perspective, a unified entity gave CAL greater standing and leverage to re-negotiate more attractive terms with their suppliers. Moreover, CAL was able to save on operating costs, since they no longer needed two separate marketing or administrative departments to run the business. Crucially, only requiring a single management team meant that CAL could save on expensive management salaries.

The consolidation resulted in notable margin improvements for CAL compared to its predecessors, as shown below:

-

Revenue grew at a CAGR of 11.8% for CAL from FY10-FY12 compared to 5.7% for CSL and CMB should they have been combined from FY03-FY07. This was off the back of a more focused growth strategy in the core markets of Singapore and Malaysia (discussed further in Create – Improving retail experience), and despite Indonesia and Thailand operations shutting down.

-

Gross Profit (“GP”) Margin decreased slightly to an average of 31.2% for CAL compared to 35.3% for a combined CSL and CMB. This should be primarily attributed to establishing new stores which usually take a year to become profitable rather than poor performance.

-

The Operating Profit (“OP”) Margin downward trend culminating in -0.8% in FY07 was reversed for CAL, reaching 7.9% in FY12. Consisting of distribution, marketing and administrative expenses, this drastic improvement reflects a more efficient operating structure allowing CAL to exploit economies of scale.

Raising collection rates from credit sales

The Courts subsidiaries provide Buy Now, Pay Later (“BNPL”) solutions, allowing participating customers to pay in instalments over a period of up to 60 months. As furniture and electronics are relatively expensive in absolute terms, the BNPL solutions were popular, especially in Malaysia with a lower average household income. From FY10-FY12, CAL’s credit sales as a percentage of total sales ranged from 9.2%-13.7% (Singapore) and 61.9%-65.7% (Malaysia).

However, as large-scale credit financing was then a novel concept in the industry, the Courts subsidiaries lacked the infrastructure to support a credit-heavy business model, particularly CMB. Inadequate credit controls and processes led to CMB incurring significant trade receivables and bad debt. This issue was likely to depress valuation due to (i) lower unlevered free cash flow from positive changes in net working capital, (ii) potential investor perception of poor financial management.

BPEA implemented a sweeping reshaping of CAL’s credit management approach across the customer credit cycle, as illustrated below. It emphasised the following:

-

Efficiency: BPEA strived to ensure that CAL could quickly process credit applications, such that a decision can be made using the customer’s up-to-date credit data. Under BPEA’s leadership, CAL shortened the time taken to approve credit purchases to within 2-3 days.

-

Prevention: A credit audit unit in Malaysia and a centralised Management Information System was set up to consolidate a single source of truth and detect credit anomalies early.

-

Action: BPEA introduced tele-collection centres for staff to call customers and handle overdue payments.

BPEA’s success was reflected in the reduction of CAL’s credit delinquency rate, defined as trade receivables greater than 180 days in arrears as a percentage of total trade receivables from September 2007 to March 2012. In Singapore, it reduced from 4.4% to 3.2%; in Malaysia, it reduced notably from 15.4% to 9.6%. Moreover, CAL’s days sales outstanding (“DSO”) decreased from 87 in FY10 to 83 in FY12, a marked improvement from CMB’s 184 in FY07.

Curating retail experience

BPEA pursued this avenue via three fronts. The first was to improve the product offerings at their stores. BPEA’s leadership meticulously reviewed store layouts, identifying stores due for refurbishment and layout shuffles to optimise selling space.

The second was to improve auxiliary services at their stores. Inspired by the success of CSL’s Tampines Singapore Megastore in December 2006, BPEA’s ownership saw the introduction of Megastores in Malaysia. This begun from the Mutiara Damansara Megastore in December 2007 (which closed in FY12), with 3 more introduced by the time of the IPO. BPEA ported over attractive concepts from the Tampines Megastore to the Malaysian Megastores, which have a large square feet per store and thus have the physical capacity to accommodate unique features. These included a “Countdown Corner”, which offers limited-time promotions, and “Dr. Digital”, which offers a comprehensive IT consultation service. Moreover, CAL introduced more “consumer experience” areas to all store types where customers can interact with the display products, guided by trained employees. These features contributed to helping customers make quicker purchase decisions while in the store. The effectiveness of these inventions was reflected in the growth of sales per square foot.

The third was to diversify beyond physical stores and digitalise retail. Prior to the acquisition, the Courts subsidiaries, similar to its competitors, were mortar-and-brick retailers. The potential of the Internet as an integrated marketplace had not been seriously explored, as it was mainly used as another marketing tool. With a background in internet investments, BPEA lay the digitalisation groundwork. CAL launched eCourts in December 2009, a pilot version of their online shopping platform, and re-launched it in October 2012. Besides allowing customers to directly purchase items via its catalogue, eCourts also offered certain customers the ability to use the in-house Courts credit schemes to finance their purchases. Under BPEA’s leadership, Courts became the only major electrical, IT or furniture retailer in Singapore to offer a complete online shopping experience at the time. While the IPO happened immediately after the re-launch, the novelty and efficiency of the new eCourts likely played a factor in boosting investor confidence towards CAL’s future prospects.

Cash-Out: A successful IPO

For unknown reasons, it was reported that initial plans to find a buyer for CAL were scrapped. At the time, there were no significant competitors in the region under PE ownership, presumably because such business models carry inherent credit risk from consumers.

However, BPEA eventually found success via an IPO in October 2012, which was 5.6x subscribed counting only valid applications. The Public Offer of 8,900,000 shares was 24.4x subscribed, likely due to the stock being reasonably priced at SGD 0.77/share and limited landmark IPOs on the SGX. The Placement Offer of 76,895,000 shares was 3.4x subscribed, indicating that BPEA’s earlier plan to find a buyer failed not due to the lack of interest in CAL, but rather likely due to factors such as an unwillingness to accept control risk.

We estimate CAL’s enterprise value to be SGD 574.7m post-IPO, based on the reported total outstanding shares and share price as well as FY12 debt and cash figures. This represents a healthy 5.84x valuation increase from the SGD 84m the consortium paid to acquire all the shares in the Courts subsidiaries.

Deal #2: Navis Capital Partners’ RM459m Investment in SEG International Bhd

In May 2012, Malaysian private markets investor Navis Capital Partners (“Navis”), via 2 GPs, acquired a 27.8% stake in SEG International Bhd (“SEGi”). Founded in 1977, SEGi operates SEGi University & Colleges, one of Malaysia’s largest privately funded university education providers serving 16,000 students across 5 campuses. It was listed on Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad in 1995 and transferred to the Main Board in 2004.

The acquisition was then seen as a coup for Navis, as SEGi was experiencing significant growth in share price due to a remarkable 28% YoY increase in revenue from FY10 to FY11. This was driven by increased student enrolment, launching new courses with overseas partner universities and the expanding homegrown programs. Shareholders were hopeful that Navis’ capital injections and operational experience would help SEGi scale further. Unfortunately, an unsuccessful value creation strategy led to the share price dropping and Navis finding a lack of attractive exit opportunities. Having gradually exited shares in SEGi, Navis fully exited its remaining 20.6% stake to founder Clement Hii in April 2024. Navis reportedly only made a 1.45% IRR on their investment over a 12-year hold, below the 20% threshold they had targeted for Navis MGO I GP Ltd, one of the funds used for the investment.

Control: A failed take-private initiative

Navis pursued a traditional PE playbook: to implement operational growth mechanisms in a majority stakeholder and de-listed position which would make SEGi more attractive in a future sale. As a public company, SEGi was paying out nearly half of its net profit as dividends at the time of acquisition. By privatising SEGi, Navis and Hii wanted to recycle SEGi’s profits into capital expenditure instead, without being beholden to other shareholders.

Navis intended to de-list SEGi by acquiring the remaining shares along with Hii, then the largest shareholder at 29.8%, via a Mandatory General Offer (“MGO”). An MGO makes it compulsory for an acquirer who holds at least 33% of a company to offer to buy the remaining shares at minimally the highest price the acquirer paid for shares in the past 6 months. It is standard practice in Malaysian M&As and is preferred by acquirers as it offers an efficient way to provide a transparent price without having to negotiate with several minority shareholders concurrently. However, if the MGO fails, the investor is stuck with a significant and relatively illiquid minority stake.

Navis triggered the MGO by acquiring 27.8% shareholding primarily from two of the biggest minority shareholders, Cerahsar Sdn Bhd and Segmen Entiti Sdn Bhd (together the “Datuk Vehicles”), which serve as investment entities of wealthy Datuk businessmen. This brought the total effective shareholding between Navis and Hii to 57.6%. Navis’ negotiation with the Datuk vehicles was relatively straightforward, likely because they were investment entities which target a fixed “hold” term and have a mandate to recycle capital.

However, buying out the other shareholders proved difficult. Navis offered the same share price to the remaining shareholders at RM1.71 per share. Independent Financial Advisor (“IFA”) Affin Investment Bank Berhad (“Affin”) assessed the fair valuation of SEGi shares to be at RM1.88-RM2.29, owing to (i) share price of SEGi being ~RM1.81 at the time of the offer, and (ii) an uncompetitive share price against peer comparables and precedent transactions.

Unlike institutional shareholders with significant minority stakes, smaller minority shareholders are largely not constrained by fixed holding terms. Since smaller stakes are also more liquid, they were under no significant pressure to liquidate their shares. Thus, smaller minority shareholders are much more sensitive to how much they are receiving per share. Presumably encouraged by the strong upward trajectory of SEGi’s share price, not enough shareholders accepted the offer to privatise SEGi.

Believing that the initial offer was fair based on internal calculations and believing in Navis’ and Hii’s joint ability to implement value creation initiatives, Navis did not submit an improved counteroffer. While Navis was able to increase its shareholding to 41.7% at peak by acquiring some minority shares via the MGO and converting warrants, they were never able to privatise SEGi.

Navis’ failure to privatise SEGi reveals how the traditional strategy can be curtailed at the control stage owing to regulatory factors outside the investor’s reasonable control. Under the MGO model, Navis was forced to either (i) drop the offer or (ii) offer a higher amount than what the market previously validated was fair, compromising their ability to meet their IRR target.

Create: A difficult business model to monetise

SEGi competed in the highly saturated Malaysian tertiary education market. It lacked the cachet of Malaysia’s most established public institutions such as Universiti Malaya (“UM”), Universiti Teknologi MARA (“UITM”) and Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (“UKM”), who could offer heavily subsidised tuition fees and better employer recognition. SEGi positioned itself instead as a competitor to the many private universities in Malaysia, both local (e.g. Sunway, Taylor’s) and international (e.g. Monash, Nottingham). SEGi’s business model hinged on attracting students who were required to pay higher fees. It primarily focused on courting 2 demographics: (i) international students who were ineligible for subsidised education and (ii) medical and nursing students who needed to pay to access specialised vocational training.

Malaysia was seen as a more affordable destination for many international students to pursue university education in compared to many developed countries. With Malaysia targeting 200,000 international students by 2020 and SEGi managing to increase its international student population by 87% year-on-year in FY11, SEGi looked set to sustain its upward momentum. Navis attempted to capitalise on this trend by acquiring a piece of land for RM52.3m in FY12 in Selangor to develop an international school. While SEGi had not drawn down any bank debt in the past 3 FYs, it incurred an RM44m debt in FY12 to fund this endeavour.

However, the international student revenue stream was quickly put in jeopardy. In April 2012, a month before Navis invested in SEGi, the Ministry of Higher Education established the Education Malaysia Global Services (“EMGS”), a one-stop portal for foreign student visa processing. The system intended to streamline the visa process to within 14 days and further encourage international students to study in Malaysia. However, the EMGS soon experienced bureaucracy and mismanagement issues, with the visa application process often taking 3-6 months. More importantly, the EMGS was widely criticised for its profit motives by dramatically increasing the costs for international students to apply for a student visa, as follows:

-

Visa processing fee: All student visa applicants were mandated to pay RM1,000 for visa processing, with a yearly RM140 renewal fee. If a student decides to change their major within the university, they will be charged a new processing fee of RM1,000.

-

Medical screenings: All student visa applicants were mandated to pay RM250 per medical check up, which had to be conducted every year.

-

Medical insurance: All student visa applicants were mandated to buy medical insurance, with packages ranging from RM500-RM850.

Where a foreign student only had to pay a total of ~RM400 previously to apply for a visa, they now had to incur a minimum of ~RM1,750 to do so, excluding the additional ~RM390 per year for visa renewal and medical screening. Allegations of further hidden fees raising the cost for one student to ~RM3,200 circulated. Furthermore, private colleges also claimed that the EMGS mandated them to pay a RM1,000 mandatory processing fee to submit an application for an international student. These changes made it a far less attractive proposition for international students to study in Malaysia, with SEGi’s international enrolment dropping in FY13 and barely increasing from 35% of students in FY15 to 40% in FY22. Accordingly, SEGi’s revenue dropped by -17% from FY12 to FY13, with revenue never recovering back to FY12 levels.

Navis found itself in a difficult position with SEGi. With the quantity of international students decreasing, SEGi could have attempted to make up for the loss in revenue by increasing tuition fees per student. However, with intense competition from other reputable universities, hiking prices was not a sustainable strategy. Switching focus to courses with higher margins was also difficult as SEGi had already carved out a niche in high-margin medical and nursing programs. Even if such a course were to exist, it would take years for SEGi to execute a successful pivot. It would have to attract the right teaching talent, procure the appropriate equipment and infrastructure, design a curriculum, market the course to students, and build a solid reputation in the course. Facing a lack of feasible options, Navis scrapped the international school project, selling the land in FY16.

This incident reveals how PE investors expose themselves to significant risks with their investments and may not always be able to carry out their value creation initiatives due to extenuating circumstances beyond their control. This issue was amplified with the private higher education business model, which is heavily reliant on a particular student demographic to generate consistent revenue.

Cash-Out: Relying on alternative equity activities

Facing a lack of willing buyers and a disappointing drop in share price, Navis looked to alternatives to recoup their capital while waiting for an opportune moment to sell its stakes. Below is an estimated breakdown of the capital recovered, with alternative equity activities making up 75.7% of Navis’ total return:

Aggressive dividend payout policy

Dividend yield was relatively consistent from FY12-FY14, ranging from 0.07 to 0.11. By pivoting away from growth investments, Navis was able to generate more proceeds to pay dividends in FY15, leading to a surge in dividend yield to 0.17.

Navis funded another large-scale dividend payout in FY18 via a sale-and-leaseback strategy of its fixed assets. This financial engineering resulted in a spike in ROU assets from none in FY17 to RM136.8m in FY18, and a corresponding decrease in PP&E in the same FY from RM110.8m to RM87.6m.

In FY17, while traditional dividends were not paid out, SEGi announced a capital repayment of RM0.15 per ordinary share (~RM108m total), via reducing the par value of each ordinary share in SEGi from RM0.25 to RM0.10. This provided Navis and other shareholders with an effective dividend return on their shares without having to sell them. Although Navis did not have majority control over the company, other shareholders were likely aligned with Navis’ motivation to pursue such equity activities owing to the falling share price and bleak growth prospects.

Share buybacks

In FY20 and FY22-FY24, SEGi embarked on a share repurchase campaign. This coincided with rumours that Navis and other shareholders were contemplating selling their stakes amidst interest. Therefore, apart from returning immediate capital to Navis, share buybacks may also have potentially been motivated by a desire to keep share prices attractive by boosting earnings per share (“EPS”), in preparation for a sale.

Authors:

Vernon Goh

Vansh Goel

Uttkarsh Poddar

Jatin Singh Kodial

Jeun Minju